The text on the side panels tells of the Terrible Angels who tumble from heaven and commence terrifying a village where people tremble and a cat cries in fright. These contorted, winged and tailed creatures appear as silhouettes above the text on the two side panels, like odd decorative embellishments. The avenging Virgin sounds a threat: “Do not mistake me for a vessel,” she says – a blunt reference to the male view of the female as a utilitarian object, a void – “I am the devouring flame.” If the Terrible Angels don’t get the message immediately, they soon will. She dispatches them by cutting off their wings and tails.

Obviously, the “annunciation” depicted here has nothing to do with the Christian belief in the Virgin Birth. What Faye proclaims through her imagery and much of the story is an unambiguous statement of the power of womanhood. But at the conclusion of the tale, she offers the sole hint that the aftermath of her Virgin’s brutal actions may not be unmitigated happiness in this “village of idiots”: in the end, the misshapen cat weeps aloud. Can the cat alone see what the dim humans cannot – that female ferocity of this order may not always be viewed with equanimity?

Lauren Faulkenberry’s The Heart Wants What it Wants was inspired by the Greek Furies, merciless earth goddesses who punished those who committed crimes such as perjury, arrogance and, especially, murder. The book consists of three volumes titled Smolder, Galvanize and Devour, the last invoking Egyptian mythology. Each section is printed on a single 18” x 24” sheet that folds map-like into a six-inch square. The trilogy and its accompanying text, taken from a short story written by the artist, explore themes of heartache, longing, loss, and expectations and, in the artist’s words, |

The Heart Wants What it Wants

Lauren Faulkenberry |

|

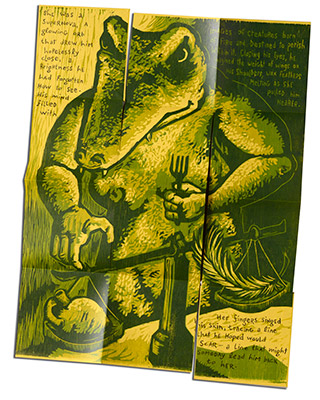

The looming anthropomorphized figure in the image shown here is both mysterious and imposing. She has the face of a crocodile, human hands and ponderous breasts. The reptilian head represents the Egyptian funerary deity Ammut, the “Devourer” or “Eater of Hearts” who was part crocodile. In Egyptian mythology, the hearts of the deceased contained the sum total of the deeds of their lives. One’s fate in the afterlife was determined by a direct and irrevocable method: the “Eater of Hearts” weighs the organ against the “feather of truth.” If the heart is more evil than virtuous, it’s heavier than the feather and Ammut would have her feast. In Faulkenberry’s image the toothy and fiendishly eager crocodile is weighing a heart and a feather on a large iron scale, and since this creature is holding a fork, the viewer can guess what the destiny of this particular heart will be.

The artist employs reduction woodcut and photopolymer plates. The technique allows for bold and simplified images, which heightens the elemental drama of her tightly cropped scenes. Her figures are somber, thanks to the use of monochromatic color, but they are never so bleak that the fairytale atmosphere is dispelled. The hand-lettered text jauntily works its way through the empty spaces around the figures, telling the story of a sideshow performer who longs to free herself of all her oglers, lowlifes who have no compunction about judging her. The book, says the artist/author, is about how we navigate through life, a theme that might be applied to Medea and Jason’s checkered journey. The text in the upper left-hand corner of the crocodile image could easily describe Medea as she sits in her dragon-pulled chariot, literally and physically above it all: “She was a super nova, a glowing orb that drew him hopelessly close, a brightness he had forgotten how to see.” Sometimes, reason deserts the most reasonable among us, and then, as Faulkenberry’s book contends, the heart gets what it wants. |

The heart shape is likely the world’s most ubiquitous symbol. Its first known manifestation was in the Late Stone Age when Cro-Magnon hunters scratched the symbol into rock-drawn pictograms. From there, nearly every civilization has used it, from ancient Egypt to Greece and on through the Middle Ages, the Renaissance and into modern times, until today when it has, among countless other places, landed unceremoniously on a plethora of bumper stickers. |

Title Divine

Miriam Schaer |

|